Yearbook 2000

Slovenia. Slovenia underwent a government crisis in the summer when Prime Minister Janez Drnovšek resigned in protest against Parliament opposing his economic reform policy, which aimed to get the country into the EU as soon as possible. Until the general elections in mid-October, Andrej Bajuk was head of government for an expedition minister. The electoral law was changed slightly so that a 4% barrier was introduced in order to prevent small parties from entering Parliament. Drnovšek’s party The Liberal Democrats (LDS, Liberalna demokracija Slovenije) went ahead and got 34 seats by Parliament’s 90. Two of them are dedicated to the Italian and Hungarian minorities. Drnovšek took a full six weeks to get the effective government he wanted and to get the necessary support in Parliament. In addition to the LDS, the government consisted of three smaller parties.

- ABBREVIATIONFINDER: Offers three letter and two letter abbreviations for the country of Slovenia. Also covers country profile such as geography, society and economy.

Slovenia was one of the first candidates for EU membership, but a number of issues still remained to be resolved, including: a small number of border disputes with Croatia.

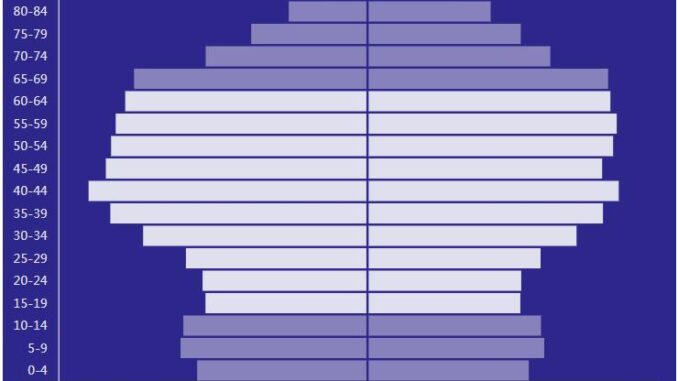

Population 2000

According to COUNTRYAAH, the population of Slovenia in 2000 was 1,987,606, ranking number 145 in the world. The population growth rate was -0.030% yearly, and the population density was 98.6950 people per km2.

Literature

The upward pace of Slovenian literary culture becomes even more sensitive in the last years before the Second World War. The number of writers is constantly increasing and the publication of their works provides editorial equipment which, in relation to the small number of Slovenes, can be considered perfect. The number of translations is growing; the literary horizon becomes wider, the process of de-provincialization of Slovenian culture more rapid, while the prestige of German culture as the main intermediary between Slovenes and abroad is decreasing more and more.

Instead, the antagonism between traditional cultural positions, Catholic and liberal, secular, anti-traditional assumptions still persists. But the Slovenian cultural movement is no longer exhausted in it: there are many escapes, and above all due to a greater and more immediate artistic commitment. It is felt both in poetry and, especially in the work of Anton Vodnik (Skozi vrtove, Through the gardens, 1941), aims more and more at an essential expression, without the discursive digressions and sentimental accents dear to the precursors, as much as in the narrative, where the matter drawn from regional environments overcomes contingency by means of a robust naturalism, fleshless, full of humanity. Thus in the numerous novels by Meško Kranjec (born in 1908), which at times deal with the life of the proletariat with excessive lyricism, and above all in the vigorous art of Prežihov Voranc (pseudonym of Lovrenc Kuhar) whose stories (Samorastniki, I without a father) on the hard fate of the mountaineers of southern Carinthia contain, in their crudeness, some of the most successful pages of Slovenian fiction. In the drama, which still remains the Cinderella of Slovenian literature, the re-enactment of the famous peasant insurrection led by Matija Gubec (1573) due to Bratko Kreft (Velika Puntarija, The great rebellion, 1937), who also distinguished himself as director.

The occupation of the Slovenian territory, which took place in April 1941, resulted in a complete interruption of any cultural activity in the area annexed by Germany and a stagnation in that subject to Italian sovereignty. The only center, Ljubljana, which gathers the few surviving writers around the magazine Dom in Svet. Of note, among these, A. Gradnik who in 1942 published a new collection of verses (Pesmi or Maji, Canti su Maia). Quite numerous are the narrators whose work is affected, however, by the difficulties of the moment in the choice of topics (historical, folkloristic). After September 1943 the situation worsened, even in Ljubljana, while the area occupied by the partisans became increasingly active, even in the literary sphere.

Since there are not many, nor of particular value, emigrated writers, the resumption of activity, once the war is over, is not difficult. The same nestor of Slovenian poetry O. Zupančič published in 1945 a new collection of verses (Zimzelen pod snegom, The periwinkle under the snow). Anton Vodnik is back in the breach. However, it is the poems of the partisans (Vladimir Pavšič, Karel Destovnik, etc.) that give the imprint to the new literature. The story reaffirms those who had already emerged before the war, first of all Prežihov Voranc, whose talent appears even more mature both in the novel (Jammica, 1945, but written in 1941) and in the short stories (Na š i mejniki, Our border stones). Among other things, the sketches of Karel Grabeljšek, Za svobodo in kruh (For freedom and for bread) and several dramas (Raztrganci, Straccioni, by Matej Bor; Roistvo z nevihti, Birth from the storm) bring us back to the life of the partisans. Vitomil of Župan; Velika preizku š nja, the big exam, Mira Puc, etc.) that seem to portend a fruitful interest in the dramatic genre.